One of my most favorite cookbooks is "Ancient Grains for Modern Meals".

Award winning Author Maria Speck combines her German father's love for hearty grains, and her Greek mother's culinary talents in dishes that make you grab your shopping bag, hop on the bike or in the car, and drive to the next natural food store to buy those ancient grains, veggies and fruits for Maria's mouthwatering meals.

Normally I consider a cookbook worth its money, if it contains at least one recipe I really like to cook. "Ancient Grains" has so many, that I still haven't prepared all the ones I want to try. (No, I DON'T get a commission!)

A few of the dishes are breads, among them the Aroma Bread. A no-knead bread by trade, its evocative name spiked my interest, and my love affair with the spicy loaf began.

"Ancient Grains" is very user friendly, with detailed, easy to follow instructions, no sophisticated culinary equipment needed. No-knead breads meet these expectations, a mixing bowl, a wooden spoon, a clean kitchen towel, a Dutch oven, and you are all set.

These low maintenance breads don't want you to slave over them, they are free spirits, and perfectly willing to go and develop themselves, if you give them enough time (and a little bit of yeast.) They show their gratitude by rising eagerly, and tasting better than many other loaves that had been kneaded, slapped and punched into submission.

You have the choice between a crunchy, and an XX-crunchy Aroma Bread. If you opt for the super chewy, you need to soak whole grain berries for several hours, before mixing them into the dough. This is definitely no impulse bread, so plan to bake it 24 hours ahead.

Maria called her loaf "Aroma Bread" for a good reason. This truly aromatic loaf is not for the faint hearted! But in our old home country Germany breads are often flavored with coriander, fennel and caraway, these herbs are even commonly referred to as "Brotgewürz" (bread spices.) You can use them whole, or coarsely ground.

|

Bread spices fennel, caraway and coriander |

As easy as no-knead breads are to mix, handling wet dough always remains a bit of a challenge. And here comes the sticky wicket: the dough has to be shaped into a loaf, and transferred from the mixing bowl to a place where it can rise. And, after that, it has to be turned out into a piping hot Dutch oven.

That leaves you with two choices: either to lower the bread gently into the pot, risking nasty burns (aka Baker's Badge of Honor). Or you let it drop from a secure height - and have your bread sigh and deflate!

Maria solves the problem by having you scrape the bubbly fermented mass onto a well floured countertop (flour is your friend, creating a barrier between the sticky dough and its surroundings), so that you can fold it into a round.

Then you place the loaf on a floured kitchen towel, fold the corners over it, and, voilà, you have a cozy proofing place. Of course, it takes a rather amorphous shape from being bundled in a kitchen towel.

My first bread went into a large, oval Dutch oven (I didn't have a smaller one), and eagerly spread to fill the void.

|

My first Aroma Bread - shaped like a roly poly! |

Baked into a rather flat loaf, it reminded me of those little things that scurry away when you lift a stone. But when I took the first bite, my eyes glazed over. My flat roly poly bread tasted awesome!

The next time I decided to set the bread more boundaries, changing its Armadillidiida appearance. Instead of proofing it simply in a towel, I used my pretty brotform to contain it.

|

Proofed in a rising basket, the bread is round but still... | | |

It came out of the oven nice and round, but still... way too much room to spread during the baking.

Alas! My main source for discounted kitchen gadgets, Home Goods, was letting me down when I needed it most. Still without the right sized pot, I decided to experiment with a free-standing, self- contained sourdough version, made with pre-doughs à la Peter Reinhart's "Whole Grain Breads".

|

Aroma Bread made as free-standing loaf (with sourdough) |

My hearth baked sourdough loaf turned out beautiful. Though I couldn't find much difference in taste, this method is a good alternative for people who either have no Dutch oven, love wild yeasts, hate wet doughs, or prefer to bake their bread as free-standing loaf.

The next time I visited Marshall's (another treasure trove for kitchen stuff) I found a snazzy turquoise cast iron pot in just the right size - for half the price! And soon was mixing the ingredients for my fourth Aroma Bread - again the no-knead version.

And out of the oven came (TATAAA!): the perfect Aroma Bread - looking just as good as it tasted!

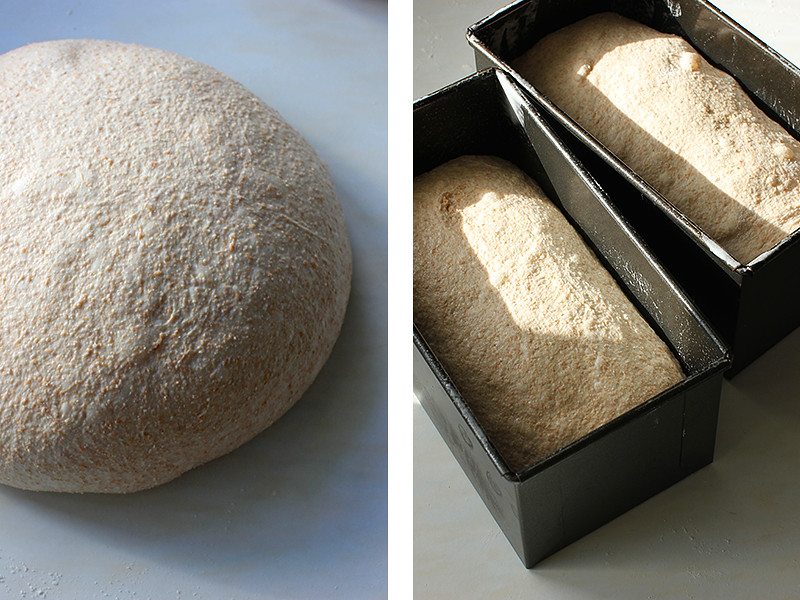

The last task left to do for inquiring minds, was to try the sandwich version of Aroma Bread, baked in a loaf pan. A cold cut-friendly shape, and the easiest way to make this wonderful bread. And it has an additional benefit: you can bake more than just one loaf at a time. (My customers will be happy!)

|

Aroma Sandwich Bread - the easiest version |

COMMENTS:

- If you use the optional whole grain berries (I made the bread with and without, both versions are great) add more salt: 9 g/0.3 oz instead of 7 g/0.25 oz.

- Instead of sunflower seeds you can also take pumpkin seeds (or a mixture of both.)

- Toast the seeds, before adding them to the dough.

- For an easier, risk free transport of the proofed bread into the hot pot, use a large piece of parchment paper as a sling to lower the bread gently into the pot. You don't have to remove it.

AROMA BREAD 1 (2-pound) loaf

Grain Berries (optional):

1/2 cup whole wheat, rye, kamut, or spelt berries

cold water, for soaking

Dough:

340 g/12 oz whole spelt flour (3 cups)

107 g/ 3.75 oz whole rye flour (1 cup)

57 g/2 oz coarse or medium stone ground cornmeal (1/2 cup)

67 g/ 2.35 oz sunflower or pumpkin seeds, toasted (1/2 cup)

35 g/ 1.25 oz flax or sesame seeds, toasted (1/4 cup)

2 tbsp. aroma spice blend*)

7 g/ 1 1/2 tsp fine sea salt (or 9 g/0.3 oz if using whole grain berries)

1 g/ 1/4 tsp. instant yeast

all soaked whole grain berries (if using)

475 g/2 cups cold water

cornmeal, for sprinkling

*) Aroma spice blend: mix 6 tablespoons whole coriander seeds with 3 tablespoons each fennel and caraway seeds (enough for 6 loaves).

DAY 1

In the morning, place whole grain berries in a bowl and cover with at least 1-inch cold water. Cover, and leave at room temperature to soak. Before using, drain them through a strainer (by the way, the soaking water is an excellent fertilizer for your plants.)

|

Mixed dough - I used black sesame seeds for a nice contrast |

In the evening, whisk together all ingredients for the dough in a large bowl, except for soaked grain berries and water. Scatter grain berries on top, and add almost all the water. Stir with a dough whisk or wooden spoon until all flour is hydrated. (Dough will be wet and sticky, if not, add a bit more water.) Cover with plastic wrap, and let sit at room temperature to ferment for 12 - 18 hours.

|

Overnight the dough grows to a puffy, swollen mass |

DAY 2

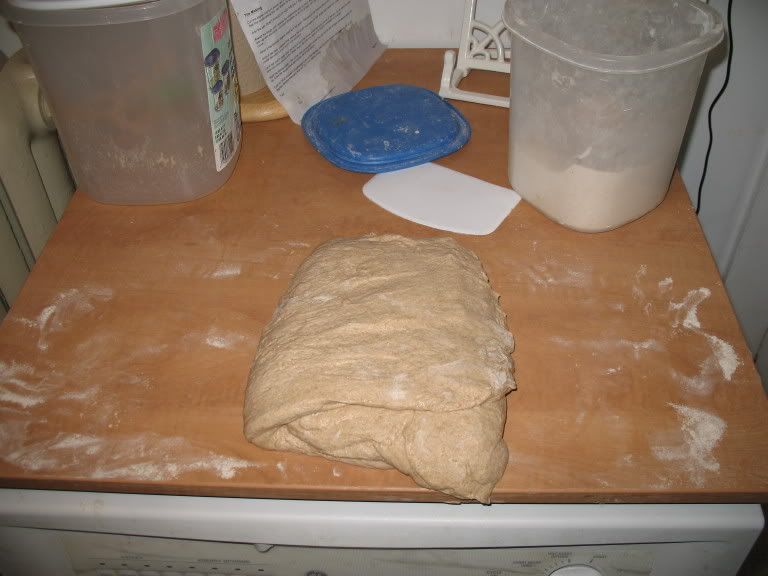

Use a rising basket, (or improvise by placing a clean kitchen towel over a basket or bowl.) Sprinkle with fine cornmeal (other flours work, too). Generously flour your work surface. Using a bowl scraper or rubber spatula, scrape the stringy, bubbly dough onto the work surface.

|

Scraping out the fermented dough you will see its spongy structure |

With floured hands (or two oiled bench knifes or bowl scrapers), fold dough exactly 4 times, always towards the center, from the top, the bottom, the right and the left side. Turn the dough package around and place it, seam side down, into the towel lined rising basket. Sprinkle with cornmeal or flour, cover with a kitchen towel, and let it rise for about 1 hour.

After 30 minutes, position a rack in the bottom third of the oven, and preheat oven to 475ºF. Place a 4 1/2- to 5 1/2-quart cast iron pot or Dutch oven (with lid) on the rack to heat up.

When the dough has grown about 1 1/2 times its original size, poke it gently with your finger. The dimple should not fill up again (it can come back a little bit, but should remain visible). If not, wait another 15 minutes.

|

Fitting snugly in the Dutch oven, the bread will rise more than spread |

Remove hot pot from the oven and open the lid. Gently turn out the proofed bread from the rising basket into the Dutch oven, seam side up, guiding it with your hand, (or turn it out onto a parchment paper and, holding the paper on both sides, gently lower the bread into the pot (with paper).

Cover with the lid, and bake for 30 minutes. Uncover, and continue baking for 20 - 25 minutes, until the loaf is nicely browned, sounds hollow when thumped on the bottom, and an instant thermometer, inserted in the middle, registers 200ºF.

Remove bread from cast-iron pot and transfer it to a wire rack to cool.

AROMA SANDWICH LOAF

Grease a 9 x 5-inch loaf pan with oil, and sprinkle it with 1-2 tablespoons of flax- or sesame seeds. After folding the risen dough, place it, seam side up, right in the prepared loaf pan. (My suggestion: brush top with water, and sprinkle it with more flax- or sesame seeds.) Let it proof as described.

Preheat oven only to 425ºF, placing an oven proof pan or broiler tray for steaming on a the lowest level to heat up.

When loaf is proofed, place in the middle of the oven, pour 1 cup boiling water in the hot steam pan , and bake loaf for 30 minutes. Remove steam pan, rotate bread 180 degrees for even browning, and bake it for about 30 minutes more, or until it registers 200ºF.

Let loaf cool in the pan for 5 minutes, than turn it out onto a wire rack (if it sticks to the pan, loosen it with a butter knife or spatula.)

AROMA SOURDOUGH BREAD

Starter:

64 g/2.25 oz rye mother starter (100%hydration)

205 g/7.25 oz whole spelt flour

124 g/4.4 oz lukewarm water

Soaker:

57 g/2 oz coarse or medium ground cornmeal

75 g/2.65 oz whole rye flour

92 g/3.25 oz whole spelt flour

168 g/6 oz water

4 g/0.15 salt

Final Dough:

all soaker and starter

43 g/1.5 ozwhole spelt flour

5 g/0.2 oz salt

1 g/1/4 tsp. instant yeast

67 g/2.35 oz sunflower- or pumpkin seeds, toasted

35 g/1.25 oz sesame seeds, toasted

2 tbsp. aroma spice blend (see original recipe)

182 g/6.4 oz water, add more as needed

DAY 1

In the morning, stir together all ingredients for soaker. Cover, and leave at room temperature.

Mix all starter ingredients at low speed (or by hand) for 1 minute, until all flour is hydrated. Knead for 2 minutes at medium-low speed (or by hand.) Let rest for 5 minutes, then resume kneading for another minute. Cover, and leave at room temperature.

In the evening, mix all ingredients for final dough for 1- 2 minutes at low speed (or by hand) until all flour is hydrated. Knead at medium-low speed (or by hand) for 4 minutes, adding more water as needed. Dough should be very tacky and not dry to the touch. Let dough rest for 5 minutes, then resume kneading for 1 more minute. (Dough should be tacky, but not sticky.)

Gather dough into a ball, and place it in a lightly oiled bowl, turning it around to coat it with oil. Cover well, and place it in refrigerator overnight.

DAY 2

Remove dough from fridge 2 hours before using, to warm up. (It should have risen nicely overnight.)

Preheat oven to 500ºF, with bread stone and steam pan.

Transfer dough to lightly floured work surface, and shape into a round. Place boule, seam side down, in a floured rising basket. Sprinkle with more flour. Cover, and let it rise for 45 - 60 minutes, or until it has grown 1 1/2 times its original size, and a dimple stays visible when you gently poke it with a finger.

Turn bread out onto a parchment lined baking sheet (or use a peel) and place it in the oven, pour a cup of boiling water in the steam pan and reduce heat to 475ºF. After 10 minutes, reduce heat to 425ºF. Continue baking for another 10 minutes, rotate bread 180 degrees, remove steam pan, and bake for about 30 minutes more, or until it is nicely browned, sounds hollow when thumped on the bottom, and registers 200ºF.

Cool on wire rack.

|

This Aroma Bread was made with whole kamut berries |

You can also follow Maria Speck on facebook or on twitter (I do!)

(Reprinted with permission from Ancient Grains for Modern Meals by Maria Speck, copyright © 2011. Published by Ten Speed Press, a division of Random House, Inc.)

Submitted to YeastSpotting

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white. For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit. Here's what it looks like after kneading.

Here's what it looks like after kneading. And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

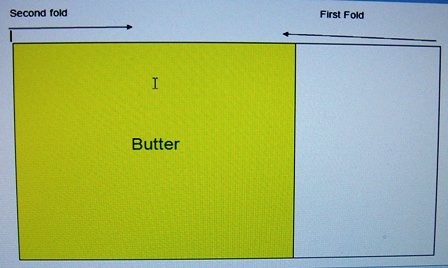

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet). Stretch it to about twice its length.

Stretch it to about twice its length. Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal. Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.