Yeast Water & Other Wee Beastie Bubbles (No Math)

There is a Chinese proverb, of which, I am very fond:

The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their right names.

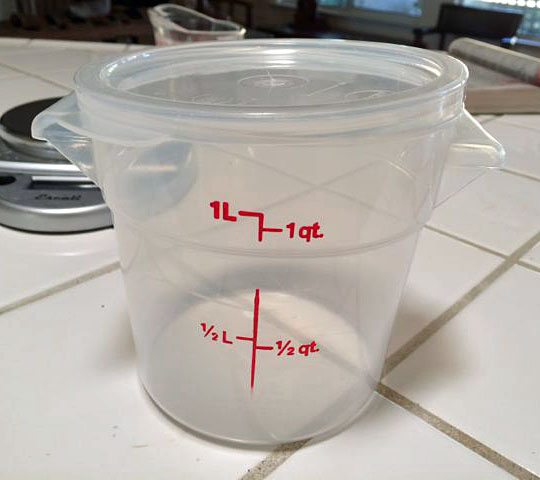

a Highly Active Culture of Apple Yeast Water

Having no delusions of being wise, I often go ahead and refer to things, for which, I have never found a proper name. However, I do try to state the meaning that I think they may deserve.

*** Some terms and the meanings I place on them when I use them.

Yeast Water (YW)... a specific instance of:

A quantity of nearly total water, which contains an active culture of microscopic life forms that will consume various nutrients and release carbon dioxide while doing so.

Yeast Water, Yeast Water Levain (YWL)... in general, intended, or already mixed with a gluten type flour:

A culture started from any type of YW that is mixed with flour and used in the same way as Sourdough Levain or Commercial yeast.

AYW, RYW, PYW, CYW, GYW, etc.... abbreviations for what is used to maintain the YW culture, such as:

Apple YW, Raisin YW, Prune YW, Clementine YW, Grape YW, etc. Used where the 1st letter's meaning should be clear to anyone.

Dust, as in apple dust, raisin dust, etc....

The accumulation of particles on the bottom of a YW culture, resulting from small parts that the culture has reduced to separate "dust" parts.

Highly Active Culture... general usage.

A Yeast Water culture that shows large amounts of activity - CO2 creation - can be in the form of bubbles rising in the actual water of a YW jar, or in a levain, which would be judged exactly as one would judge a sourdough levain.

Strong YW... general usage

Only measurable by testing growth when mixed with at least a A-P flour level gluten. This would apply to most YW that is being stored in a fridge, although, if returned to room temperature, the indications of a Highly Active Culture may re-manifest themselves.

Wild Yeast... general usage:

Any of the countless species of eukaryotic micro-organisms (over 1,500 species currently described, according to Wikipedia [1]) excluding those used in Commercial Yeast and known as Baker's Yeast, as well as Brewer's Yeast - both of which are Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and have been used for thousands of years (See Wikipedia [1, 2] ) There is no earthly reason, that I can think of, which would justify your needing to remember any of those technical terms...

Wee Bonnie Beasties (WBBs)... my personal usage

Any of the Wild Yeast that I might find useful. Sorry, but as the writer, I do have some prerogatives.

*** General Thoughts about Sourdough and Yeast Water - as far as our usage here.

All I need to know, and therefore, all I care to touch upon here, is how do I understand the cultivation, care, and usage of Yeast Water (YW) to the extent that I get the levains that will aid me in making foods I bake, &or eat - I do eat banana levain without the baking step and occasionally drink some fermented beverages..

Think of these Wild Yeast, for a moment, as if they were humans. You can find different groups that like different music, or different foods, different climates, etc. There are different groups of Wild Yeast that like wheat, others rye, others apples, grapes, etc. I think you see the point. But, they all need a source of the foods that they can eat, or that their companions can convert into foods that they can eat, and in hard times, they will eat things that they would probably not prefer to eat.

Unlike humans, Wild Yeast and their companions don't normally have drilling equipment, and while they often can be transported by air currents, they do not have wings to pick and choose locations. So, if chance places them where there are the sugars, starches and whatever that is needed for these Wee Bonnie Beasties (WBBs) to survive and multiply, then there is a very good chance that they will do just that.

Those great survival places are, more often than not, on the outer surface of commonly grown food sources. The same ones that humans often like, and for the same reasons that the WBBs like them - they are good sources of sugars, starches, and flavors - and low sources of deadly compounds (the latter consideration does not necessarily apply to humans).

Now, let us consider where these few fanciful premises can take us:

1/ The world is full of concentrated sources of these WBBs.

2/ They are there for your finding and taking.

3/ With some trial and (perhaps,) error, you should be able provide a home and diet that will keep both you and your WBBs happy.

4/ They will rise your doughs, and uncomplaining will die so that you may bake your daily bread.

5/ It is not too likely that they will remain that happy, if you force them to change their ways.

6/ Your WBBs are happy and healthiest on their original diets, and if you shift the diet, there is a very good chance the new WBBs - that come in with the new food you provide - will take over and the originals will diminish, even disappear completely.

The last item - "6/" - means that Apple Yeast Water (AYW) can shifted into a sourdough (SD) and that SD into a banana levain (BL) and the BL into a sour-rye levain (SRL) and even converted back into an AYW... Assuming you had strange tastes in what you liked to spend your time doing.

*** The Skin Game...

None of this is new., and the methods of starting a sourdough culture are filled with examples of people using the facts - without necessarily connecting the dots. Nancy Silverton has pushed using grapes to start a sourdough culture [3]. Dan Lepard says to use raisins, currants, and whey. [4] In an hour you could no doubt find any number of other examples of "Helpers to get a sourdough started".

What most of these have in common is that they start a YW culture long enough to establish an environment to foster the growth of the WBBs found in wheat flour. In my first Apple YW culture [5] I used a ¼ tsp of potato YW to jump-start the apple YW fermentation.

You do not need to be a "health nut" to realize that the skins of most commercially sold fruit have been treated

with chemicals to kill "everything except humans" ( not sure about the "except' part of that statement ). So, if you feel you must start from scratch, and use the skins of your source item, and then I would say buy from a source of untreated fruits or vegetables. Once you have any Wild Yeast culture - Sourdough, or Yeast Water, you never need to use skins again, and there are other benefits, I find, to using only the pure flesh of the fruits. Although, I will admit the "garbage disposal" approach of skin, cores, and table scraps, etc. will work to create a YW culture.

*** Do Not Be Afraid to Experiment ...

If you do not try things, you will only have "book learning". I would think, that anyone, which only had book learning would be much the poorer for the lack of the real life complement . Book learning is great, but not to the exclusion of life's lessons.

*** Why Not Just Use a Sourdough Culture and Be Done With It?

Well, I don't know. Why do anything different? Why use Sourdough and not just commercial yeast? Perhaps to learn how to do new things, perhaps, of the increase the range of options that new methods might offer you. These types of decisions are personal choices - choices each of us have to make for ourselves.

For me, there is also the fact that the general absence of the "Sour", as in sourdough, is desired at times. The fragrance from various YW levains is a worthy addition to the palette that I can use to paint the flavor of a bread, and the colors of different YW can add visual appeal to the baked goods - bread, or any other items.

In addition, there are differences in how individual types of YW levains behave. Some people have observed much faster rises with raisin YW (RYW) in certain cases, I find differences in the temperature effects on AYW, as compared to SD levains.

I also find there is the greater ease in the maintenance requirements for my AYW than there is for my SD culture. I love SD, and would never knowingly give it up. However, SD gives me one family of flavors and crumb colors, YW gives me a wider range of everything. I also have had what I consider as great results using a mixture of SD and AYW to create a bread with superior flavor, tang, color, and moistness - all based on my taste, of course, not necessarily to your taste.

But, I am not using my time writing this to play salesman. I could care less if you use Yeast Water, but two things have brought me to try to write this: First, I find - perhaps well intended - postings that are full of statements based upon fantasies (at best), and information that is only creating more "Baker's Legends" and secondly, I find more and more of my personal time being spent answering the same questions over and over. While this is a time consuming task, to the extent that I can write down these answers in a referenceable posting, the less future time that will be spent on those same answers.

*** How Does One Start a Yeast Water culture...

Well that depends on several things, but in general:

1/ Choose the type of YW you want initially. I would suggest picking one that others have had good results at starting. For that, I would say try one of these three types: Grape, Raisin, or Apple, although, feel free to try anything that turns you on.

2/ You will need to start from scratch only if you have no source of existing Sourdough, or Yeast Water cultures. Since all you need to jump-start a culture is a very small amount of any existing culture, I am sure anyone you know that has a culture could give you a part of teaspoonful of their culture to get you started.

3/ Starting with, or without, a jump-start culture:

a/ Take a clean glass jar that has a lid. I find short squat a POOR choice, and jars taller than wide a BETTER choice.

b/ Fill about one fourth of the jar's height with your raisins, or crushed grapes, or your apple slices.

c/ Add water that is chemical free. Fill that jar about half full. I find having the fruit filling only half the volume of water is convenient for the following reasons. Raisins initially sink and as the YW starts developing, raisins will start to form bubbles and then rise, grapes tend to be a mixed bag as to floating initially, while apple slices float initially, but when really depleted they often become "waterlogged" sink to the bottom. In any case, having a section that is more or less a clear water area offers greater opportunity to notice changes that start to occur in your YW culture. This is even more true when it is a fully mature and active culture.

d/ If you wish, you can add a small amount (½ tsp.) of honey, or sugar, but it is not necessary with sweet fruit at first, but would be with vegetables.

e/ IF Jump-starting ONLY:

e-1/ Using an existing YW: add a teaspoon full of the active existing YW to your new starting YW jar,

e-2/ Using an existing SD: ½ teaspoon of SD to cup of water, stir to dissolve the SD in the water and wait for half hour to get some settlement in the mixture. Then, extract a teaspoon of the top portion of the water mixture and add it to your new starting YW jar.

f/ Place a lid on the jar, and leave the jar out of direct sunlight, at room temperature (RT), or up to about 82ºF (27.8º C)

g/ Once a day (more often will not hurt) remove the lid, and stir to release any CO2 and to add oxygen to the solution. Some people find a vigorous shaking of the jar helps. It may, I have never tried it.

h/ If after 4 or 5 days, you do not see bubbles starting to forming, raisins or grapes floating, add another sugar or honey treat. If after 7 days you see nothing, throw everything out and find a new source for your fruit purchases. Start over.

*** After the Bubbles Flow...

Once you have convincing evidence of the YW becoming active, you can make your first proofing test. After all, the only proof of a worthwhile leavening culture is in the rising of the dough. So make your first YWL (YW levain). I would do it something like this:

1/ Find a small glass container, something very much like a typical morning fruit juice glass, with close to vertical sides. The straighter the container's sides, the easier it is to judge how much the levain has risen.

2/ If you weigh the empty glass and record the weight for future reference, it might come in handy. Use your tap water to see about how much a quarter of a glass of water weighs. If it is about 40 to 50 ml (grams), or about 1½ ounces, that would seem a good enough amount. Empty the glass.

3/ Measure out something close to that weight in the YW from your culture (replace the same amount of water back into the culture) and also measure an equal weight of A-P flour. Combine the YW and flour in your "test beaker", mix the two ingredients and place a rubber band around the glass at the level of the mixture's top surface. Place it in a warm location where you can check for activity and place anything - like a piece of light cardboard on the top to cover the opening - to keep anything from falling in and to minimize evaporation from the mixture.

4/ check the level, as compared to the rubber band's location to see if it is rising. If it raises to a level equal to the twice as high as the rubber band in 4 or 5 hours you have a very active levain (and YW culture) if it has not risen at least half that much in 24 hours, then your culture is not ready to use yet. In between those extremes, you make your own judgment calls.

*** After Your Proof of Life on Mars...

Okay, you now are the proud owner of a Yeast Water culture. You have the information needed you make new types of YW, should you wish to. You should realize that the characteristics of your YW will take some time to know well, and that changing the way you feed it, or adding different types of materials into the culture will all change anything you have learned about it - just as switching the A-P flour in a White Sourdough levain to a diet of rye will make it radically different in its behavior, so too will switching from apples to prunes change the characteristics of your YW. Using certain fruits will make any YW worthless for use in bread making - these are a few: kiwi, pineapple, mango and papaya.

I strongly recommend you read the materials on TFL and elsewhere before making any changes in your culture's feeding and care. Here are a few places to start such readings [6, 7, 8, 9].

*** Apple Yeast Water (AYW)...

From here on, nearly everything is specifically meant to apply only to my AYW and SD cultures, although, I will touch on some of my observations that I made with other YW types. However, as I have said above, different YW types may have different characteristics, and often do.

So, for example, if you want specifics on RYW, search TFL on "teketeke" or "daisya". If you want info on AYW, search TFL on "hanseata" or on "RonRay" and if on a wider range, search TFL on "yeast water", &or the references listed at the end of this writing.

Of course, if you are looking for deep information on the nature of SD, search TFL of "Debra Wink", who knows more facts about sourdough WBBs than anyone I ever encountered.

*** Some Q & A that have been posed in the past...

= Q

...Now that I have my RYW proofed , should I just keep that and use it like I do my SD?

= A

...No, keep your yeast water away from flour, until you want to use it for baking...

= Q

...Okay, but why?

= A

...It appears that anything the grows and offers nutrients on its skin/surface/husk/etc. will attract wild yeasts, Labs, and who knows what else. different wee beasties will find different nutrient sources preferable to others. So, your raisin yeast water (RYW) will get competition from the beasties that love flour, and soon you will not have sweet RYW, but sourdough.

= Q

...You said you use 3 builds to make your YW levain. My SD works fine with one or two. Why use more.

= A

...I used the straight method on one of wao's YW breads and it took 16 hours to rise. With SD, generally, you've done refreshes and have a good feel for just how active the SD is. If, like many people, you keep YW in the fridge, until you want to use it; you have a very poor basis to know just how active it is. It is simple for me to take a small amount (10 to 20g) of highly active YW from my active culture and add it to an equal amount of A-P flour and in a few hours have proof positive of strong growth. Using that when it is between 60% to 80% risen and moving to Build #2 gives a strong growth and guarantees that the Build #3 will provide exactly what I planned for in rise times and volume of my breads. No 16 hour surprises anymore.

= Q

...Can I get a sour YW by keeping it in the fridge too long?

= A

...I can only tell you what I have experienced:

1/ If I start with my AYW & Flour, and use AYW (not tap Water) in all builds, I have never gotten a sour levain - even after a week in the fridge.

2/ If I start with my AYW & Flour, and use tap Water (not AYW) in all builds, I have never gotten a sour levain after 3-builds - even after a week in the fridge.

3/ If I start with my AYW & Flour, and use tap water (not AYW) in all builds, and then retain some of that levain to back slope a new series of builds (built on the old levain) I have started to get a sour by the 6th build. All 6 builds being built largely at 51ºF/10.6ºC in a wine bottle fridge.

In other words: One can convert an AYW Levain into a normal WSD by maintaining an initial YW Levain in the same manor as a sourdough culture is maintained. My guess is that the continuing refreshments of wild yeast in the flour, without any fresh YW allows the flour-loving wild yeast to take over the culture.

4/ If I start WSD (White Sourdough) Levain, and use my surplus AYW from the fridge, instead of tap water, in my builds, I can build a SD-AYW Levain that is both sour and has a beautiful fragrance and makes a sweeter, more moist loaf. It has become a favored method of mine.

5/ I have never found a condition where the sourness decreased with increased time - either in, or out of a fridge.

6/ THIS MAY BE of relevance... All of the above is with Apple Yeast Water and KAF A-P flour. Since we know that each type of flour is likely to have a different group of "favorite" wild yeast living off of it, all of these results might very well be different if the flour type changed. For instance, if you used Rye flour, I would not be at all surprised if you had different results. Thus, with your different formulae, you may well be creating different conditions than those that I have been dealing with.

= Q

...How do you know your AYW is slowing down, or needs food, and such?

= A

...I use the bubbles as a measure of the activity. A slow down, usually is for one of these reasons:

1/ The pressure got too high (because I tighten jar the lid too tight). If so, there will be swishing with foaming when the pressure is reduced by removing the lid.

2/ The water has gotten too alcoholic (I do not consider that "sour", but you might) and that water goes into the fridge to use in levain builds - other than the first build. If you cannot tell alcohol by smell, taste it.

3/ The WBBs want their sugar cube "fix" (I give one cube about every 4 to 7 days, and whenever I change water).

4/ The apple slices have little left to give. (depending upon the apple type, 8 to 10 days).

BTW I have 2 jars that have been maintained this way for at least five months, and never cooled, nor refrigerated.

5/ When the apple slices sink, you know the activity is very low. The slices float, when fresh, but as time passes they become more waterlogged, and need the bubbles to hold them up !!!

Now, I was talking about my AYW (apple yeast water in those points. But it should provide a background for any wild yeast culturing - with adjustments for the oddities by "beastie types"

Here is an image of the bubbles rising in my AYW culture. They are difficult to photograph, and often I need to use a magnifying glass to see them clearly. The streams of bubbles can be very small, fine, bubbles, but they start in the apple dust at the bottom and stream to the apple slices at the top. Of course, when a sugar cube is dropped in, it sinks into the apple dust at the bottom. So, there is a lot of sugars in the material at the bottom.

= Q

...What IS your favorite fruit water? Why is it your favorite?

= A

...Well, I would call it Yeast water, not fruit water - vegetables work well, too. When I was fairly new with YW experiments, I thought I liked Clementine YW best. But Apple YW was a close second choice.

Clementine lost out more for practical considerations: I crushed the sections and only added those parts and the juice. (I found the skins of citrus, if used in YW made tastes I distinctly dislike).

Of course, any source that is highly seasonal, is not a good choice for one's "standby" YW. Grapes, raisins, and Zante Currants are all reliable year round sources, as is/are potato flakes (instant potato). Some sources must be avoided, if it is bread you wish to use the YW in - such as the warning I posted elsewhere: "Certain fruits should not be used for yeast waters intended for leavening bread. They are those fruits (or vegetables) that contain Actinidain (or actinidin) kiwi, pineapple, mango and papaya. This protease enzyme breaks down protein. If you make a yeast water from these fruits, you can still use it as a meat tenderize, but NOT in your bread dough."

I discovered that prune juice worked well to make a YW, but turned out making a dense crumb that I didn't care for very much. It did make a bread that visually could pass for a very dark rye.

Which brings up the coloring agent aspect that YW can play. Clementine and apple give a very nice soft golden tint, as well as a nice fragrance.

For me, AYW won.

Before I give the final considerations, why apple won for me, let me shift to another consideration, and that is Starting vs. maintaining a Wild Yeast Culture.

In nature, it is the skins that usually hold the highest concentrations of wild yeast. The dusty film on the skins of grapes and blueberries are wild yeast. In the modern day world, fewer and fewer skins of fruit and vegetables that one buys in the market have not been treated in one way or another to kill or remove anything on the skins. So, it becomes a bit harder to start a YW from scratch, and potentially, much less healthy to add unwashed skins to the YW. Fortunately, the skins are not necessary in maintaining an established culture, nor are they necessary if you have any type culture existing.

Since, if you have any Wild Yeast Culture, you can start a different one by jump-starting the new one. Just as feeding a pure banana purée to SD can create a pure Banana levain, or feeding rye flour to SD can get a Sour Rye, likewise, adding a small amount of raisin YW (RYW) to a jar of skinned apple slices covered with water, will get you an AYW from a RYW in about 1, or 2 days.

Of course, if you once have an AYW culture, you have no need to ever use any skins. The WBBs will slowly build "apple dust" on the bottom of the jar's clear gold-tinted water in the middle area and floating apple slices on the top. The "apple dust" seems to be that greatest concentration of the wee beasties and while I maintain some always in the culture, it adds an extended moistness to a bread. I enjoy using the "discard" apple slices (when replaced by fresh ones in the culture) mixed with raisins, honey, brown sugar as a baked apple desert - much like my Banana levain gets used as a treat.

= Q

...How can you keep from dumping your apple dust when you change water, or use the AYW for levain?

= A

...I use a baster, just a common supermarket type, but the top squeeze bulb is smaller than most. Cleaning is not a problem, since it is only used for the AYW, and I fill a quart plastic container in the sink before using the baster to extract the AYW. As soon as the extraction is complete, I simple suck the baster full of clean water from the plastic pail, shake well and squirt it into the sink drain. Repeating that 3 or 4 times is all the cleaning required and the baster is allowed to drain/dry vertically in the rack at the sink's edge.

Surplus AYW is saved in tall jars that were once olive jars and kept in the fridge's door, and used it in Build #2s and #3s of levain builds. Thus, normally, this only requires me to need 10 to 20g of fresh AYW from the active culture's water - which is replaced at once with fresh water out of the same baster that had just extracted the used amount. That AYW, of course, is what I use to make the Build #1 of any new levain build.

There is no water loss from the active culture, except what I remove - as in the above use for new levain starts. Other than that, what gets removed is nearly all water when the water gets too high in alcohol, and that is what I use to form the fridge maintained surplus.

= Q

...So simple and it sounds like you really only have to attend to it once a week....or do you toss in a sugar cube sometime before you do what you have just done?

= A

...I enjoy watching the small streams of bubbles raising from the "apple dust" and racing up to the undersides of the floating apple slices. Several times a day, I generally pause to watch them for a second, or two. It is good to open the jar one or more times a day, and just mildly stir the apple slices - the parts exposed to the air are effected differently than those that are not. Stirring also ensures that the lid was not too tight - would not want too much pressure to build up in the jar.

Of course, to stir, is to shake off bits that become the "apple dust", as well as mixing the existing dust, thus, reducing the clarity of the AYW, so I generally do this as the last act of the day. This way the AYW has overnight to regain its clarity back before I see it in the morning.

I mentioned earlier, the signs of reduced activity in a culture, and when no other basis for the decline in activeness is found, I generally add a sugar cube. This addition, generally isn't more often than once, or twice a week, but that changes, depending on how active the culture is, and how fresh the apple slices are.

*** Some Concluding Thoughts...

Yeast Water is "just another leavening agent" It offers alternatives that can be used in baking leavened doughs. Potentially, every vegetable, or fruit could be used to create a Yeast Water, and each would have its own, often subtle, differences, but sometimes very marked effects on the baked goods. I strongly suggest you compare what you have known from your use of SD and commercial yeast to your new culture. Learn the differences, and how to use them. If you do not like what you find, shift to a different food source and ,thus, shift the type of YW you have, Do not assume they are all the same.

I hope to come back and offer links to more of the specific types of Yeast Water on TFL postings. But for now, I think this should help some of those interested in more information on the subject of Yeast Water Levains.

Updated:110517-10:50 The Yeast Water Examples with Photos TFL Links Only has been posted See link:

http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/23597/yeast-water-examples-photos-tfl-links-only

Enjoy, and do not let your buns get burned.

RonRay

NOTE: A PDF of this document can be found at Google Docs by using the link below:

https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=explorer&chrome=true&srcid=0B_MScoZfDZkwZDFkMmY5NWQtMTA0MS00OGE2LTllNzQtMDFkMzM1Yjg5OWZl&hl=en

*** Footnotes...

1. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yeast

2. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baker%27s_yeast

3. http://www.food.com/recipe/nancy-silverton-s-grape-sourdough-starter-316306

4. http://www.amazon.co.uk/Handmade-Loaf-Dan-Lepard/dp/1845333896/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1277986711&sr=1-2

5. http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/20460/banana-saga-%E9%95%B7%E7%AF%87%E6%95%85%E4%BA%8B#comment-143439

6. http://originalyeast.blogspot.com/2009_03_01_archive.html

7. http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/6012/baking-natural-wild-yeast-water-not-sourdough

8. http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/20693/culturing-growing-and-baking-range-wild-yeasts

9. http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/20460/banana-saga-%E9%95%B7%E7%AF%87%E6%95%85%E4%BA%8B

10. http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/20693/culturing-growing-and-baking-range-wild-yeasts#comment-143857