I'm posting this recipe for discussion as we have been talking about it on the Glezer firm starter thread. I have made this bread often with variations because I did not have the high-extraction flour yet. I recently purchased the Golden Buffalo flour from Heartland Mill in Kansas and it was superb. I didn’t take photos of those so will next time I make it.

The one pictured here was made using Hodgson Mill WW graham flour sifted for the WW portion (250g) and mixed with the 750g King Arthur bread flour. I’ve also made it sifting the King Arthur traditional and organic WW flours but I like the sweetness of the graham flour. Still, I think after using that high-extraction flour the flavor was so extraordinary I would choose to make it that way more often.

Mountaindog has also posted her variation on this bread here and she makes beautiful loaves of it.

http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/1806/thom-leonard-country-french-boule-recipe

This is a great recipe to play around with and it always comes out fabulous bread. Another note – I generally like to make four smaller boules but when I made them with the high-extraction flour I made two boules and they were large and fantastic.

Here are the some photos of the ones I made a few months ago (more photos here: http://zolablue.smugmug.com/gallery/2671417#141408937 ) and the recipe follows:

Thom Leonard’s Country French Bread - © Maggie Glezer, Artisan Baking

Makes one 4 pound (1.8-kilo) loafTime: At least 18 hours with about 30 minutes of active work

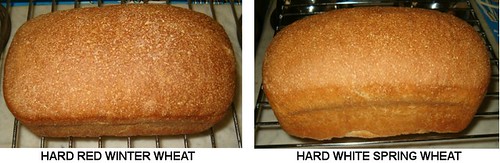

Much of what makes this bread so special is the high-extraction flour used in it. This is a bolted whole-wheat flour much lighter in color and sweeter in flavor than a whole-wheat flour (at 100% extraction), but much darker and more flavorful than a white flour (at 72% extraction).

The method I give here for making your own high-extraction flour will work best on coarsely ground whole wheat flour. If you already have a good high-extraction flour, substitute it for the whole-wheat and bread flour in the final recipe. Thom also includes a little of his sourdough rye starter in the dough, but it is such a small amount that I have bumped up the levain slightly and added rye flour to the final dough instead.

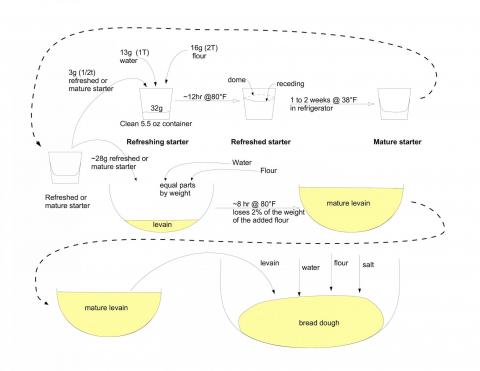

RECIPE SYNOPSIS The evening before baking - making the Levain:

25 grams (1 1/2 tablespoons or 0.8 oz) fermented firm sourdough starter refreshed 8 hrs before (17%)

140 grams (2/3 cup or 4.9 oz) water, lukewarm (100%)

140 grams (1 cup minus 1 tablespoon or 4.9 oz) unbleached bread flour (100%)

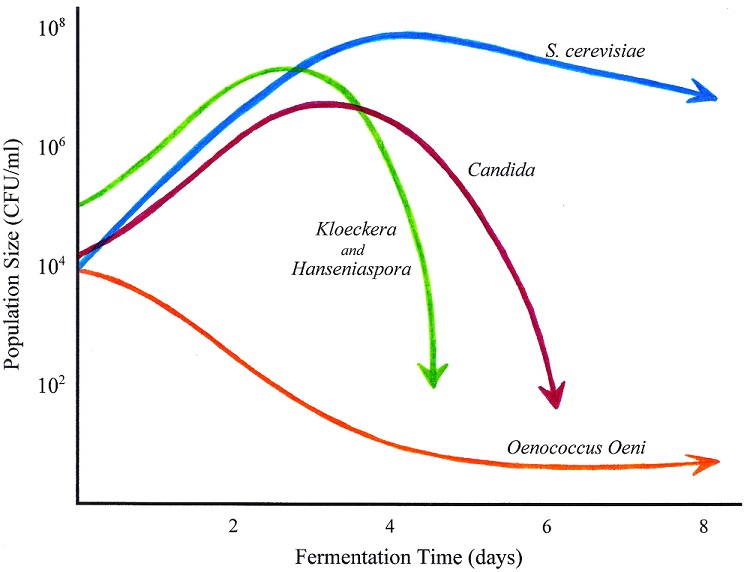

Dissolve the sourdough starter in the water in a small bowl. Add the flour and beat this batter-like dough until very smooth. Place in a covered container and let it ferment overnight for 8 hours, or until fully risen and just starting to sink in the middle.

Bake Day – Mixing the Dough:

350 grams (about 12 oz or about 2 1/2 cups) Coarsely ground whole-wheat flour, preferably milled from an organic, hard winter wheat (eventually 25%)

750 grams (26.5 oz or 5 cups) unbleached bread flour, preferably organic (75%)

30 grams (1 oz or 1/4 cup) organic whole-rye flour (3%)

660 grams (24 oz or 3 cups) water (66%)

Fermented levain (30%)

23 grams (0.8 oz or 1 tablespoon plus 1 1/2 teaspoons) salt (2.3%)

Preparing the flour:

Sift the whole-wheat through your finest sieve or flour sifter. The large flakes of bran should be caught in the sieve (use them for flouring your peel or for muffins). Measure out 2 cups 3 tablespoons (8.8 ounces, 250 grams) sifted flour. Mix this dark flour with the bread flour and the rye flour in a large bowl or in the work bowl of your mixer.

Add the water to the fermented levain to loosen it from the container.

Mixing the dough:

By hand: Pour the watered levain into the flours and stir with your hands or a wooden spoon just until a rough dough forms. Turn the dough out onto the unfloured work surface and continue kneading until the dough is very smooth and shiny, about 10 minutes. This is a lot of dough and will take some muscle. Sprinkle on the salt and continue to knead the bread until the salt has fully dissolved and the dough is very smooth and shiny.

By stand mixer: Add the watered levain to the flours in the work bowl and stir the dough together with a wooden spoon or your hand (this will make the mixing go more quickly). Using the dough hook, mix the dough on medium speed for about 10 to 15 minutes, or until the dough is very smooth and almost cleans the bowl. Add the salt and continue mixing until the dough is much tighter and cleans the bowl, about 5 more minutes.

This should be a soft, sticky, and extensible dough.

Fermenting and turning the dough:

Place the dough in a container at least 3 times its size and cover it tightly with plastic wrap. Let it ferment until it is airy and well expanded but not yet double in bulk, about 3 hours. Turn the dough 3 times at 30-minute intervals, that is, after 30, 60, and 90 minutes of fermenting, then leave the dough undisturbed for the remaining time.

Rounding and resting the dough:

Flour the surface of the dough and your work surface and turn the dough out. Tuck the edges of the dough in to tighten it, round it, and cover it loosely with plastic wrap. Let it rest until well relaxed, 10 to 15 minutes. While the dough is resting, sift flour over a linen-lined basket or line a large colander with a well-floured tea towel.

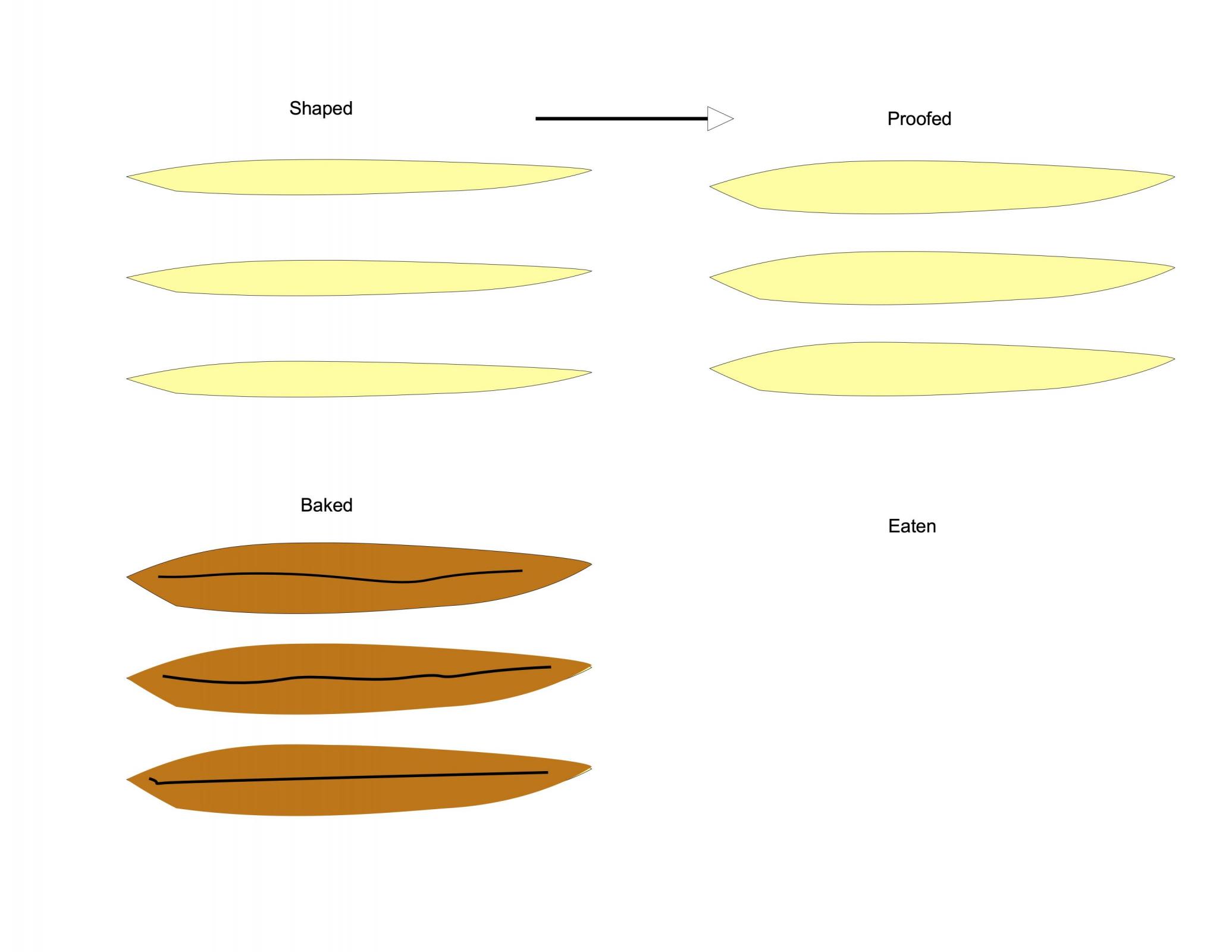

Shaping and proofing the dough:

Shape the dough into an even and tight round loaf without deflating it. Place the dough topside down in a linen-lined basket or large colander, lightly sprinkle it with flour, and cover it well with plastic wrap. Proof the dough until it is well expanded, about doubled in volume and remains indented when lightly pressed with a floured finger, after about 4 hours.

Preheating the oven:

At least 45 minutes before the dough is fully proofed, arrange a rack on the oven’s second-to-top shelf and place a baking stone on it. Clear away all racks above the one being used Preheat the oven to 450°F (230°C).

Baking the bread:

If desired, just before baking the bread, fill the oven with steam. Turn the bread out onto a sheet of parchment paper or a floured peel and slash 3 to 4 diagonal slashes and 3 to 4 horizontal slashes into the top. It will look like a skewed grid with diamond-shaped openings. Slide the bread, still on the paper, onto the hot stone and bake until the bread is dark and evenly browned all around and sounds hollow when thumped on the bottom, 70 to 80 minutes, rotating it halfway into the bake. If the bread is browning too quickly, reduce the oven temperature to 400°F (205°C), but still bake the bread for at least 70 minutes. Let the bread cool on a rack.