German baking day

At my son's school we are starting a German expat's learning group to give our children some idea of German culture, like watching Biene Maja, playing Mau Mau and .. of course... German supper, usually some bread with different toppings such as sausage and cheeses and cold meats.

This gave me the push to start investigating how to make tge breads I miss over here. It's not the multigrain ones - I have a craving for different kinds of "Mischbrot" - bread that is made up of (light) rye flour, and wheat flour. Usually it is leavened with a rye sourdough, and some yeast is added in the final mix.

The overall percentage of rye can vary from 30 to 99% (100% would be a rye bread, "Roggenbrot") If there is more than 50% rye it's called Roggen-Mischbrot, if it's less than it's a Weizen-Mischbrot.

Meister Suepke gives in his Sourdough blog a general formula for the process called "Detmolder Einstufen-Fuehrung", bread made with sourdough which has been made in a single stage (as opposed to the intricate Detmolder 3 stage process), and he also gives hints how to scale this to different wheat contents.

I found that his formula corresponds very well with many of the rye formulas in Hamelman's "Bread", so I played a bit with the ratios and was very pleased with the outcome.

== Update 23/06/2011: Added some new photos and formulas at the end

== Update 12/05/2012: Added link to Google Docs spreadsheet

Enough words for now - here is a photo of what I made for the supper tomorrow: 80% rye with soaker according to Hamelman (tin loafs, could have baked a bit longer), 60% rye after Suepke (ovals) and 30% rye after Suepke (fendu)

Here the procedure:

All breads use the same sourdough:

100% wholemeal rye

80% water

5% ripe starter

The sourdough has fermented at 23-25C for 14 hours

The doughs (The percentages are in a table below):

| Ingredient | 80% Rye | 60% Rye | 30% Rye |

| Wholegrain rye | 136 | ||

| Wholegrain rye from soaker | 111g | ||

| Light rye | 196g | 69g | |

| Wheat flour | 110g | 226g | 402g |

| Water | 125g | 192g | 213g |

| Water from soaker | 111g | ||

| Salt | 9.9g | 11.3g | 11.5g |

| Instant Yeast | 2.7g | 1.8g | 1.8g |

| Sourdough | 381g | 257g | 186g |

The procedure is roughly the same for all breads:

Mix and work the dough, rest for 30 minutes, shape, proof for 40 to 60 minutes, bake at 220C for 25 to 35 minutes (500g loaves)

The soaker for the 80%rye is prepared at the same time as the sourdough: pour boiling water over the flour, mix and cover.

The doughs with more wheat should show some gluten development.

/* Update */

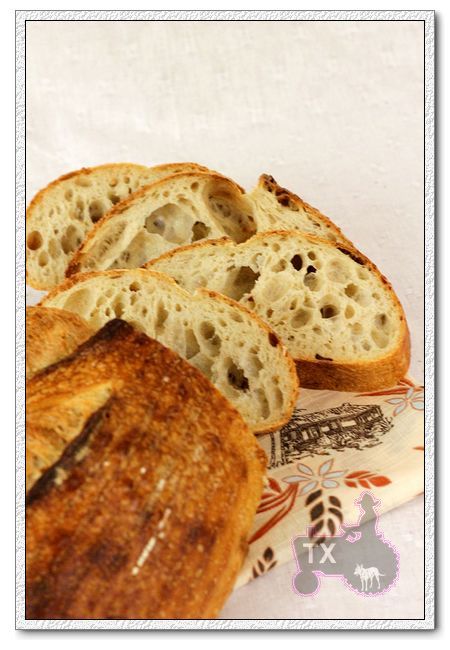

On the evening of the bake I couldn't wait - I cut the breads and posted the crumbshots above.

And I tasted them - the lighter breads are very satisfactory - beautiful elastic crumb and a rich taste with a good level of acidity - this is what I wanted.

The 80% turned out lighter color than I expected - I think I baked a bit too early and not long enough, but the taste is very promising (this bread should be cut and eaten at least 24 hours after the bake, it will get darker by then).

For reference here is the table with the percentages following Suepke's formula. I scaled the water down to 70% for 20% rye Mischbrot which works well. Sourdough as above.

Rye | 100% | 90% | 80% | 70% | 60% | 50% | 40% | 30% | 20% |

Wheat | 0% | 10% | 20% | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 70% | 80% |

Water | 78% | 77% | 76% | 75% | 74% | 73% | 72% | 71% | 70% |

Salt | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% | 2% |

Fresh yeast | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% |

Fermented flour | 28% | 26% | 24% | 22% | 20% | 18% | 16% | 14% | 12% |

Yield | 181% | 180% | 179% | 178% | 177% | 176% | 175% | 174% | 173% |

Here is the aabove table in Google Docs:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AkcYHhPxccKtdERlMzlWOEhBQ2Z5c1Z0MUZYRGVTZlE

You can export the spreadsheet as Excel (with all the formulas) and scale the dough according to your needs.

You can adjust the expected dough weight, hydration of starter, surplus amount of starter and scaling weight.

Happy Baking,

Juergen

Variations

Using the above percentages and procedures I made 3 different "Mischbrot" variations:

1. 30% Rye using wholegrain rye starter and flour and caraway (about 2%)

2. 50% Rye using light rye starter and flour, and bread flour

3. 50% Rye using wholegrain rye and wholegrain wheat. The flours for the final dough and the water have been mixed and left to soak overnight.

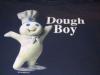

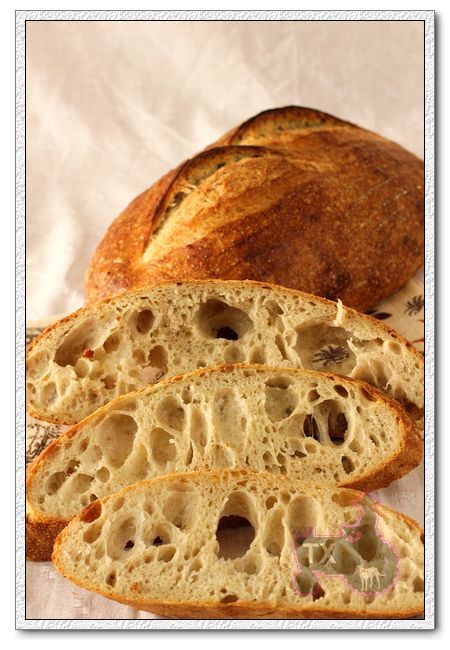

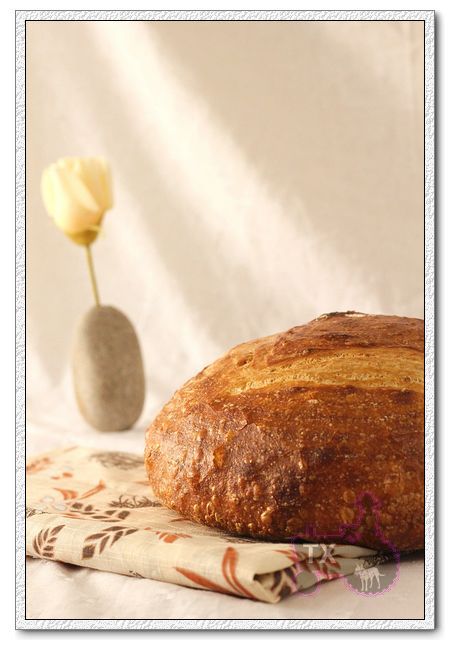

Here a photo:

The 30% rye is among the most delicious breads I've made so far. Light and hearty, and goes well even with jams, despite the caraway. (I get the feeling that I will have to bake lots of those in the coming weeks...)

The 50% mixes were inspired by my search for Kommissbrot (German army bread), which has been introduced during WW1, but found its way into the shops (and is still there). Originally it was - according to WiKi - a 50:50 wholegrain rye/wheat mix with sourdough and yeast.

The 50% rye with light flours is not bad, but a bit boring, but the wholegrain version certainly will stay in my repertoire: A very rich, complex taste with a strong wheat component and quite a bit of acid, like a mix between a 100% rye and a levain with wholegrain. The crumb feels light and springy, despite its look. I'm very pleased.