Oatmeal and Sweet Date Bread (courtesy BBGA/Team USA 2005)

Hello,

I really enjoyed the recent course I took that was put on by the Bread Bakers Guild of America, and am grateful for being a member and for having the chance to participate. Another thing I really appreciate about membership in the Guild is access to Guild's online newsletter and formula archive. There's lots of good stuff in that archive!

Today's bake is Oatmeal and Sweet Date Bread, one of the Team USA 2005 formulas the Guild provides online.

This one caught my eye last March; oatmeal and dates are two of my dear father-in-law's favorite things and I wanted to make this bread for him. This bread was very moist, and delicious with the sweet dates!

It was so good, I wanted to try making it again today (...a Team USA formula for Canada Day!

...the maple leaf is to add some Canadian content :^) ... )

Wanting to share this formula, I asked permission of the Guild to post the formula here on TFL; the Guild kindly granted permission and asked me to include this note in the post:

"The mission of The Bread Bakers Guild of America is to shape the knowledge and skills of the artisan baking community through education. Guild members have access to many other innovative professional formulas, both online and in the Guild’s quarterly publication, Bread Lines. For more information about membership, please visit www.bbga.org."

With thanks to the Bread Bakers Guild of America and Jory Downer, William Leaman and Jeffrey Yankellow, the team members of Bread Bakers Guild Team USA 2005 - who were gold medal winners that year at the Coupe du Monde de la Boulangerie!

The formula authors describe the bread and its ingredients:

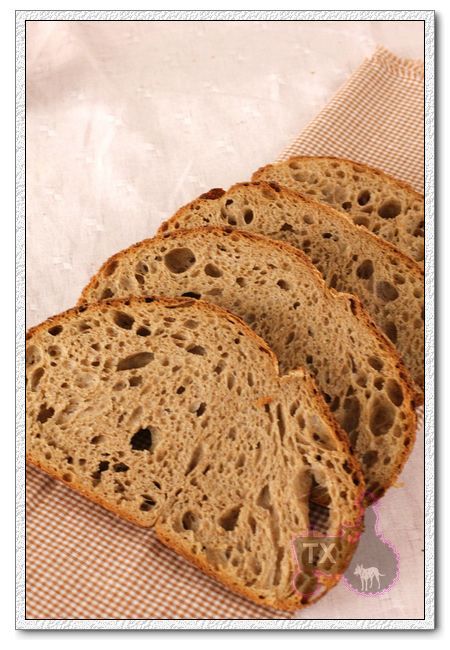

"The wide range of weather throughout the United States provides for a variety of growing climates. The warm weather of the west coast, allows for California to grow an abundance of palm trees that fruit, the luscious date. In this original formula, rolled oats, another major crop of American farmers, are complemented by the sweetness of dates. A portion of the oatmeal is fermented in a sponge. The high sugar content of the dates creates a rich brown crust that balances their sweetness. The abundance of oats results in a tight textured, full bodied crumb which is a pleasant contrast to the open crumb of the other breads."

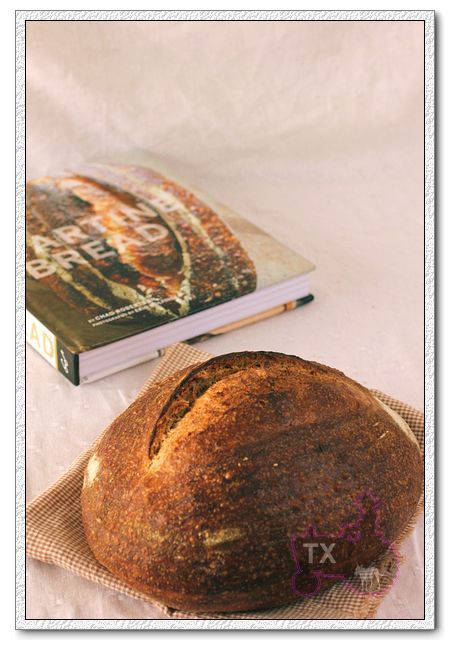

A couple of pictures from today's bake (1500 grams dough weight, 540g boule, (6) 160g triangles):

My first bake (3 boules, 1635 grams total dough weight):

This bread is made with three preferments and a soaker, but the three preferments can be mixed at the same time.

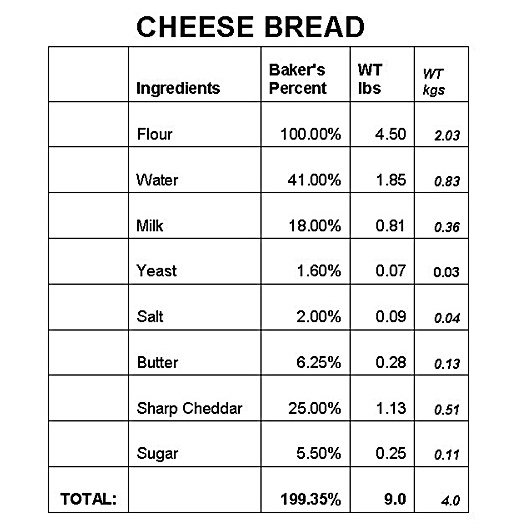

Ingredients ( for 1635 grams dough):

| Poolish | Oat sponge | Liquid levain | Soaker | Dough | Total |

Bread Flour | 120 | 120 | 60 |

| 300 | 600 |

Water | 120 | 132 | 60 | 60 | 219 | 591 |

Instant yeast | 0.12 | 0.12 |

|

| 1.5 | 1.7 |

Salt | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

| 11.5 | 13.0 |

Rolled oats |

| 60 |

| 60 |

| 120 |

Dates, diced |

|

|

|

| 300 | 300 |

White starter |

|

| 12 |

|

| 12 |

Poolish |

|

|

|

| 240 |

|

Oat sponge |

|

|

|

| 312 |

|

Liquid levain |

|

|

|

| 132 |

|

Soaker |

|

|

|

| 120 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Total | 240 | 312 | 132 | 120 | 1635 | 1635 |

I adapted the method for mixing by hand:

12 hours prior to the mixing the dough:

Poolish: Use a water temperature for 72-74F final poolish temperature; mix all until well blended; cover and ferment at 73F for 12 hours.

Oat sponge: Use a water temperature for 72-74F final sponge temperature; mix all until well blended; cover and ferment at 73F for 12 hours.

Liquid levain: Use a water temperature for 72-74F final levain temperature; mix all until well blended; cover and ferment at 73F for 12 hours.

(At 9 hours, my levain wasn't anywhere near ready...the salt taking its effect; I set the container holding the levain in a shallow basin and filled halfway with warm water; replaced with more warm water as needed; this got the levain going and it had tripled by the time the poolish and sponge were ready)

30 minutes to 1 hour prior to mixing the dough:

Using tepid water, mix together so oats are all moistened; cover, and set aside to let rest.

Prepare the dates by chopping; set aside.

"The variety of date used is flexible. It is important that they are not too soft. A soft date will blend into the dough instead of maintaining its shape, creating a dark color in the bread and increasing the likelihood of a burnt crust. The dates should be cut into ¼” pieces in preparation for mixing."

Mixing the dough:

Use a water temperature for 73-76F final dough temperature. (I started with 104F water as I was allowing for autolyse, hand mixing and resting periods during the hand mix, during which my doughs tend to cool down).

Place flour in bowl. Add 85-90% of the water to the bowl and mix until flour is evenly hydrated. Cover and autolyse for 20 minutes.

Add yeast, poolish, oat sponge, and levain to the mixing bowl. Mix with a dough whisk to combine. Cover, place in warmed proof box (to try to preserve warmth in the dough), rest 5 minutes. Dough temp.: 80F.

Oat sponge is on the left in the photo:

Add salt to mixing bowl. Mix, folding in the bowl, 50 folds. Dough temp.: 74F. Cover, place in warmed proof box, rest 5 minutes.

Fold 30 times in the bowl, then 5 minute rest as before, then finally 20 folds. Dough is lifting away from the bowl as I fold it at this point; gluten showed improved mix.

Add remaining water (80F) to the bowl, and mix to incorporate.

Add oat soaker and dates and mix to incorporate evenly.

Dough temp.: 73F (recommended to be 73-76F).

Bulk ferment at 78F for two hours, with (3) stretch and folds every 30 minutes.

Here is the dough at the end of the bulk ferment:

For the first bake I divided the dough into three parts to make boules. For today's bake, I followed these shaping instructions to make (2) triangle breads (remaining dough shaped as a boule):

Divide the dough in 160g / 5 ¾ oz pieces and preshape as a tight ball. Cover and allow the dough pieces to rest for 20 minutes.

Shape the rested balls of dough into triangles, being gentle not to degas the dough too much. Three triangles make up one loaf. Arrange three triangles together on floured linen, seam up, so that the point of one triangle rests in the center of one of the sides of the other triangle. The finished shape will have a circular appearance.

(I proofed top side up as I didn't think I'd be able to successfully flip the triangles over!).

Place the loaves in a draft free place at approximately 74° F for 30 minutes to proof.

Shaping a triangle by gently folding over three sides, towards center, pinching to seal and bring together:

After proofing:

A couple of notes about the maple leaf: I used a bit of decorative dough for this (extra dough that I froze after making my fol epi loaf awhile back. After thawing, the dough is just as good as new :^) ... a happy discovery!)

After cutting the leaf and removing the excess dough, I dusted the leaf with flour.

I used the cutter to gently! mark the boule to help with placement of the leaf.

I brushed the area where the leaf would go lightly with water, to help the leaf stick.

After the leaf was placed, I scored around it and then lightly on the floured leaf, to try to make "leaf veins".

Back to the triangles:

If proofing seam side up, turn the loaves over onto the oven loading device.

Score each triangle with two lines (I did three).

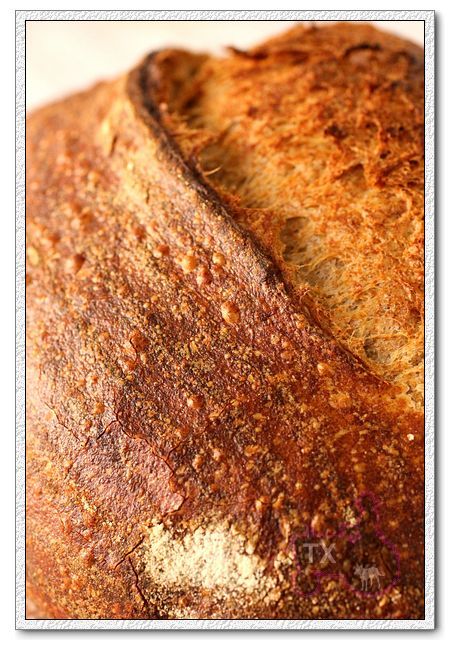

Bake with steam at 475° F for approximately 30 minutes.

Vent the steam from the oven and continue to bake for an additional 5 minutes.

(I found these were browning fast. I moved the loaves around every 10 minutes, and covered with foil and reduced to 435F after 20 minutes. 30 minutes total bake time; left in oven for 10 minutes with oven off and door ajar).

Remove the bread from the oven and allow to cool.

And lastly, a couple of crumb shots!:

Happy baking everyone, and Happy Canada Day!

from breadsong

Submitted to YeastSpotting :^)